- 110908 On My Way Home

- 111008 Welcome to the Jungle

- 111108 Unpacking Day One

- 111208 The Trip to Mopti

- 111308 Timbuktu

- 111408 A Big Day in the Desert (part one)

- 111408 A Big Day in the Desert (part two)

- 111508 Camels, Trucks, and Boats

- 111608 Niger River Beer Run

- 111708 Never Get Out of the Boat

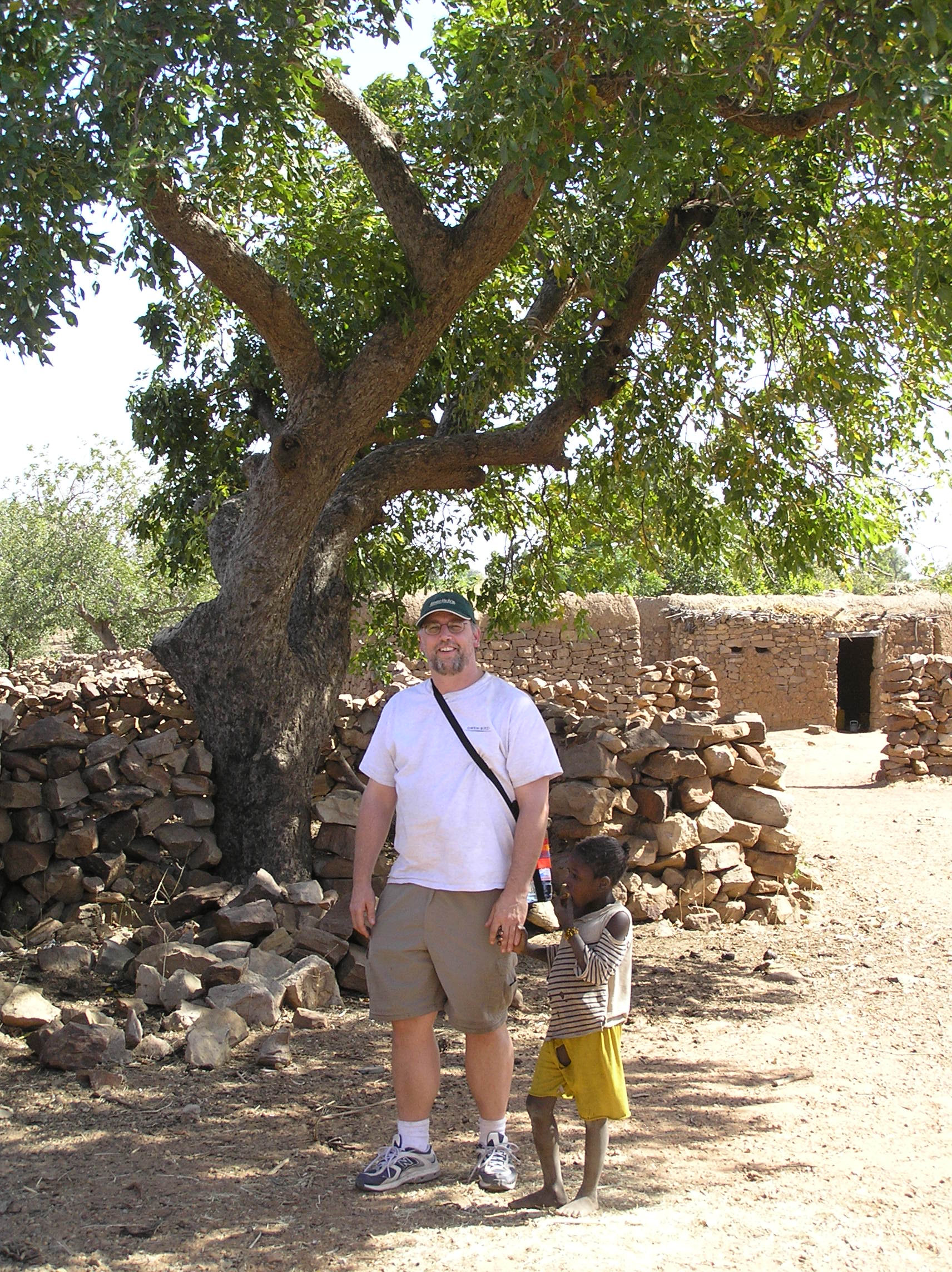

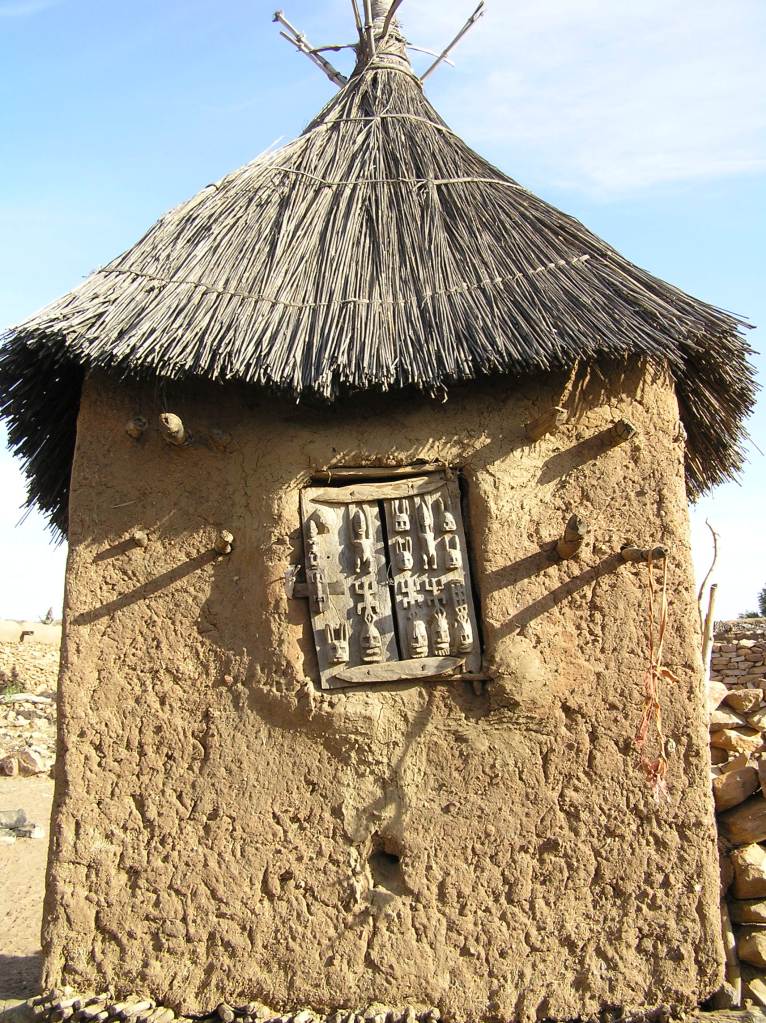

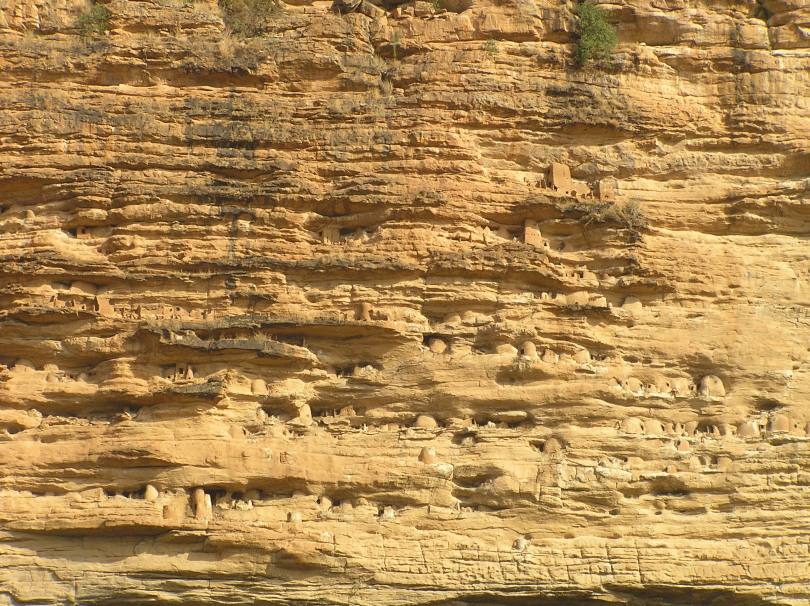

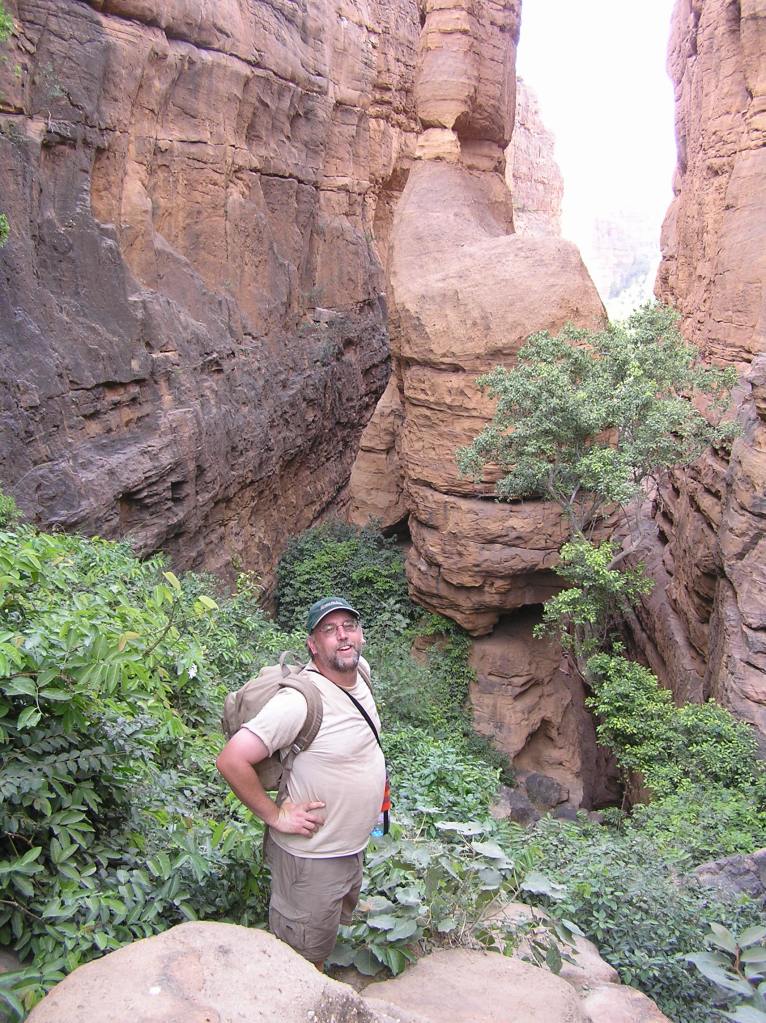

- 111808 Enter the Dogon

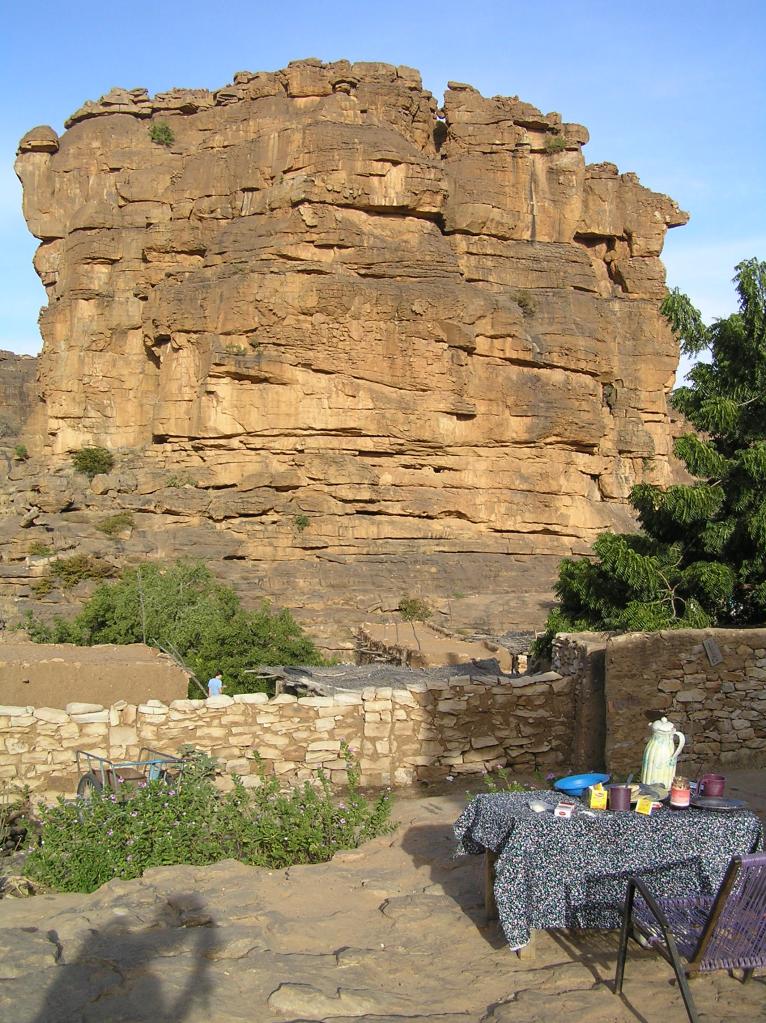

- 111908 Sand Trek

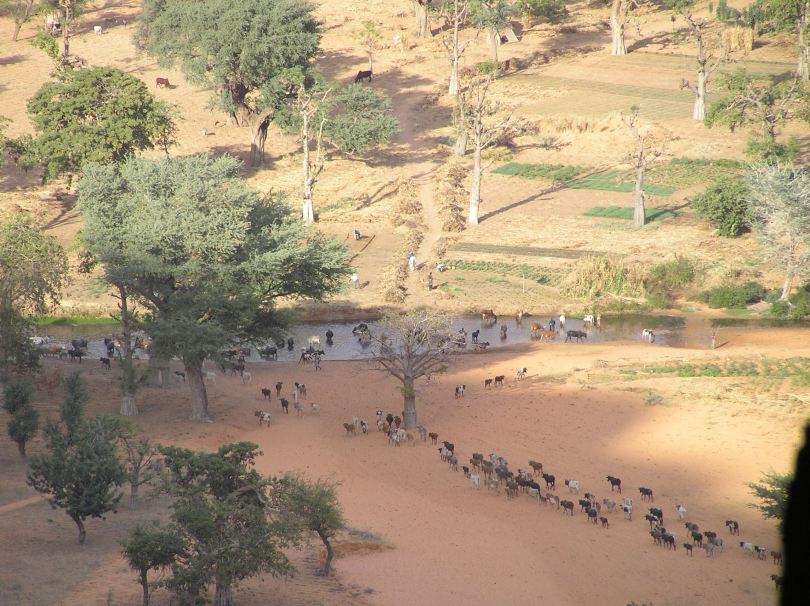

- 112008 Life in the Valley

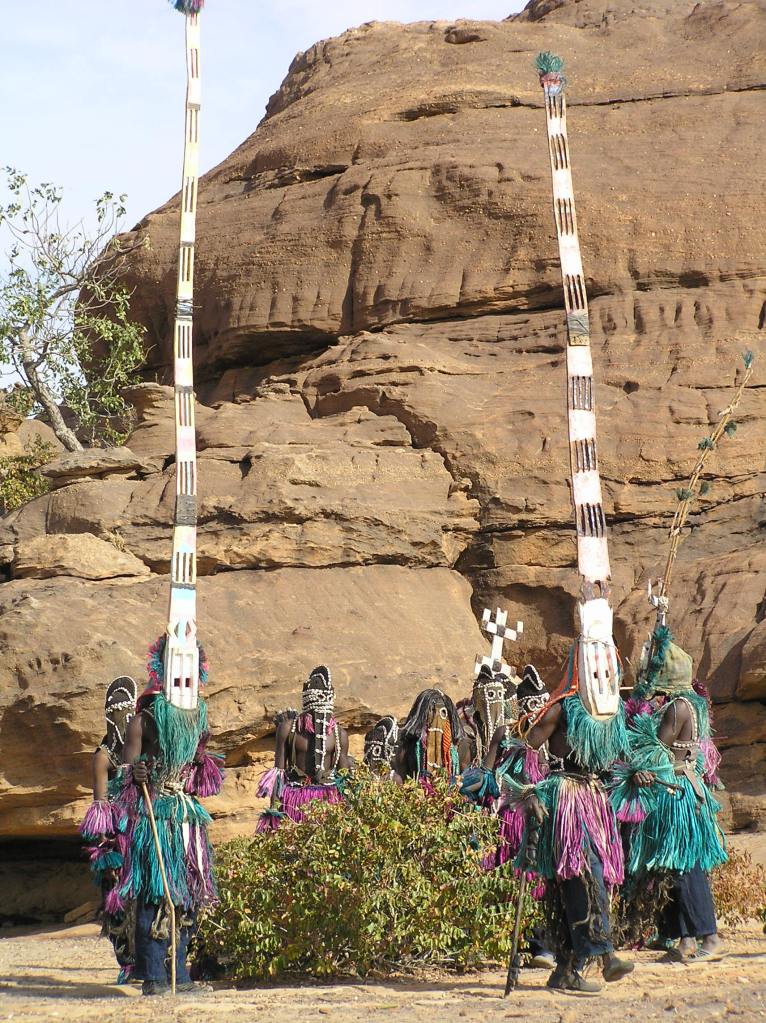

- 112108 The Party

- 112208 The Great Fall

- 112308 Music, Music, Music, Music!

- 112408 Collectif Soul

- 112508 Dit Weah and Djenné-Djenno

- 112608 The Long Road Back to Bamako

- 112708 No Problem

- 112808 Paris

- 112908 Fin, et Bonne Nuit

110908 On My Way Home

As I sat on the bus between Ottawa and the Montreal airport numbly gazing at the dark and starkly pretty Canadian landscape that fluttered by, it finally started to sink in: I was going home, back to the motherland of humanity.

For some reason I’d prepared for this, my first trip to Africa, differently than I had prepared for most of my journeys. Or, more accurately, not prepared. Usually by the time I embark on a trip I’ll have researched the destination so meticulously that I feel somewhat nonchalant about actually getting there. For this trip, however, I had done virtually no research whatsoever. So as I rested my forehead on the cold window and tried to concentrate on the blurry forest scenery outside, inside I was an anxious bundle of nerves barely concealed beneath a quiet silent surface.

I hoped a burger and a beer before takeoff would take the internal edge off. Or perhaps keeping the edge on was a better strategy? Regardless, I got my panicky bus-gazing mind set on a burger and a beer at the airport so I had one (and one).

Though I was on a budget. I hit the Burger King while m’lady made her way to the St. Hubert. We met up at a plastic table-and-chairs and wolfed down our quasi-meals before I rushed to find a bar, with just ten minutes to go before our plane started boarding. I ordered a Canadian and struck up a quick conversation with a guy at the bar who was heading the same way I was. He said he was in mining, a gold digger from British Columbia on his way to Mali for the third time. With all that experience he was clearly much more comfortable with missing planes than I because when I pounded the last of my beer and begged out of our conversation to run for the gate he just shrugged and sat there calmly toying with his cocktail.

I gotta tell you, I love Air France. The staff are friendly, the inflight magazine is hefty, they serve the best meals in the sky, and most importantly they still dole out free drinks. The only beer option was Heineken, but who’s complaining? M’lady was resting when the garçon came by so I ordered her a small bottle of red wine too. I’ve been up front on Air France before but even back in regular class they offer a myriad of entertainment choices – I decided on The Dark Knight. The seats in the proletariat section are still small, but as I tossed and grunted the night away I placated myself with memories of the dijon-style sauté of beef accompanied by vegetables and Parisienne potatoes, with fresh baguette, gouda cheese, fruit, and chocolate raspberry cake for dessert. When grinding my kneecaps into the seat in front of me didn’t keep me awake, the drooling did.

Between Montreal and Paris one loses five hours so it was 9am (née 4am) when we arrived at Charles de Gaulle for a seven-hour layover, but rather than killing time at the airport we got our butts directly on the train into the city. This marked my first visit to Paris and two things were immediately apparent: there’s graffiti everywhere and everyone talks like Inspector Clouseau. We found a cafe and enjoyed a pair of $6 coffees; m’lady ordered an omelette. The waiter was just rude enough to remind us where we were without dampening our spirits as we soaked in the street scene, which included a fair share of graffiti’d vans.

After our très petit dejeuner we visited the famed Cimetiere du Pere-Lachaise. We wandered amongst the gorgeous memorials, discovering the final resting places of Bizet, Chopin and many other note-writing notables. Popular culture* being what it is, of course the peak of the visit was the alleged final resting place of Mr. Mojo Risin: Jim Morrison. Cheesy yet necessary, the pilgrimage is complete.

Back on the metro we shared m’lady’s wee bottle of wine that we had smuggled off of the airplane and I tell you, we felt very Parisian in doing so. We arrived back at the airport with plenty of time to catch our connecting flight. The next leg of our journey was on the same airline. I eagerly hoped they were serving the same menu and made a point of staying awake to find out.

*I just noticed that the word “culture” includes the word “cult”. It makes sense I suppose, but I doubt many people associate their own culture with a cult. The cultures of others maybe, but not their own. Seems fitting though that I noticed this when typing about Jim Morrison. I’m not saying that The Doors were cult by any stretch, but Jim’s gravesite definitely looks suspiciously cult-like.

111008 Welcome to the Jungle

Generally when a plane gets close to landing one begins to see the lights of towns and cities below. As we descended towards the capital of Mali all I could see below us were scattered bonfires, otherwise I could see no light at all. We landed at Bamako’s Senou International Airport around 10pm and disembarked directly onto the runway in a sweltering night heat. As we followed the other passengers across the tarmac I was surprised to notice throngs of people spilling out of the building to greet us. I’m talking about maybe a hundred people or more, and they clearly weren’t airport employees. Once we squeezed our way inside the terminal it was clear that there was no semblance of security, sanity, or decorum anywhere. There were people everywhere I looked, and they all seemed to be yelling and waving and screaming and trying to get everyone else’s attention. The place was nuts; just complete and utter chaos.

Somehow through all the madness we found not only our luggage but also a man named Baba, who told us that he had a car waiting that would take m’lady and I to the hotel that we had pre-booked for our first night.

(Aside from this hotel our entire three-week stay in Mali was unbooked. At this point we hadn’t even looked into things like transportation, accommodations, excursions…nothing. We were the blind leading the blind straight into the Sahara Desert.)

The three of us made our way to the parking lot surrounded by a crowd of touts that kept busy trying to carry our bags and telling m’lady how beautiful she is. Baba ultimately directed us to a very beat-up Mercedes. We piled in and made our escape, headed towards Mali’s capital city.

I was immediately struck by how many open fires I saw burning alongside the road. Small garbage fires, big bonfires…there were fires everywhere. Combined with lumbering vehicles spewing clouds of black exhaust and who knows what other poisons, I can say without hyperbole that the air truly was thick. Every waft carried with it an olfactory adventure. That said, the traffic was relatively sensible, the main road was actually quite good, and there were gas stations all over the place, (the price was about a dollar per litre).

We eventually turned down, well, Baba called it a “street” but I hesitate to agree. Though I will concede that it was a somewhat level strip of potholes without any houses built on it, so close enough I guess. Regardless, the ailing car bungled along the indecipherable road and delivered us to our hotel. We were shown our room, for which we were given the choice of paying 15,000* (if we used the air-conditioning) or 7,000 (if we left the air-con turned off and agreed to only use the sad and lazy overhead fan that spun around just fast enough to make noise but not fast enough to actually create wind).

We opted for the latter (budget…remember?) and asked about drinks. The hotel guy offered to go buy us an armload of beers. He was back in a jiffy and m’lady and I dove in trying to convert our wide-eyed buzz of exhilaration and adventure into sleep-deprived alcohol-induced exhaustion. We eventually succeeded and turned in after twenty-eight hours of travel.

*At the time 1000 West African CFA francs was equal to $2.35 CDN

111108 Unpacking Day One

What can I say about my first day in Africa? It was so jam-packed with astonishment that I could easily pump out 10,000 words just on the first twenty-four hours.

(Fret not; I shan’t.)

In the morning (okay, the early afternoon) m’lady and I awoke in Mali to the first of what I suspect will be a series of hot, sunny days. In short order our de facto guide pulled up in yesterday’s beat-up Mercedes. We got in and Baba directed the driver to take us all to a hospital on the poorest side of town.

About a year earlier I had read a story in the Ottawa paper about a Canadian organization called Not Just Tourists that sends medical supplies to underprivileged countries via tourist’s unused luggage space. M’lady and I tend to travel lightly so we signed up (as a matter of fact, m’lady went on to volunteer for the organization for the next decade or more). We had brought two NJT suitcases along with us on this trip, containing between them a total of twenty-five kilos of medical supplies.

After a brief stint in the clinic’s busy waiting room we were shown in (I’ve heard it said that in the West we have clocks while in Africa they have time) and met by a doctor who quietly took the supplies off of our hands. I must admit that I felt a bit odd about the whole exchange, though I’d definitely do it again. It felt uncomfortable to sit across from a man who – against what odds and after who knows how much struggle – rose through the ranks to become a doctor in such an impoverished country and watch him swallow his pride while he accepted random, unscheduled charity of cast offs and out-of-date materials from a guy whose biggest accomplishment had been being born white in North America. Though I should stress that the doctor did not make it uncomfortable by his own actions or attitude. For his part he merely surveyed the contents of the suitcases and accepted them with shrug and a mute nod. The tension was all in my head. It was real, but it was self-imposed.

Our chore complete, m’lady and I our four guides piled back into the car and I asked them to take us to the best drum maker in the city.

When we’d decided to travel to Africa I knew immediately that I wanted to go to Mali, and it all goes back to my first two years studying music at Carleton University. Back then the mandatory Aural Training course included a weekly African drumming component and during my first two years (and for those two years only) the university had contracted a man named Yaya Diallo to lead three drumming sessions every Friday. Everyone enrolled in the Bachelor of Music program was required to attend one of the two-hour sessions each week; it wasn’t long before I asked and was granted permission to attend all three.

Yaya came on the bus from Montreal every week. He spoke French and his own native Malian language. I spoke neither and he didn’t speak English very well but I think we understood each other just fine. For example, I understood that Yaya had been born in a remote village in Western Africa and that he was raised to be a goat herder. I understood that he learned to play music from an elder in his village and that he learned to use music for healing from his mother, who had been a herbalist and traditional healer.

And most importantly I understood that Yaya Diallo was the most “pure” musician I had ever met. He made music fully, completely, and without distraction, and always with a near-sacred determination. He dispensed little praise and tolerated no excuses. Making music was Yaya’s entire reason for being and I found him enthralling. As a young, wide-eyed musician in the throes of idealized academia there was no way that I could avoid idolizing the man. I was thrilled to sit beside him (as I invariably did) for six hours every Friday.

Yaya didn’t talk very much. For his classes there were no papers, textbooks or exams (“Every time you play is a test”), and when he did speak it was usually a story about his life in the village. One day he told us how to go about purchasing a drum if we were ever in Mali. He said that when most musicians try out a new drum they will play their craziest rhythms and flail their arms around, making fools of themselves. Yaya assured us that the drum maker would only bring his poorest drums to such a person, for they knew that a showboat isn’t concerned about the sound of his instrument; for such a musician a drum is merely a soapbox to stand on.

With a smattering of English and some translating help from the French speakers in the class Yaya told us that to understand the quality of a djembe one only had to play the drum’s three sounds. A good musician will approach each drum by tilting it slightly (to allow the sound to escape from the bottom) and hitting it three times in quick succession: Boom Din Dun. The first beat tests the bass sound with an arched palm striking the centre of the skin, Boom! Second, one makes the drum’s main treble note sound with a curved hand hitting the drum’s similarly curved rim, Dun! Finally comes the high overtone that is achieved through a subtle, nearly imperceptible adjustment of the rim shot, Din!

Boom Dun Din. That’s all, and on to the next drum. When a drum maker sees you do this, the artisan will bring you his finest instruments.

As usual, I listened to Yaya in trance. At that point in my life I hadn’t been anywhere (aside from one trip to Disney as a kid) but I knew I would one day go to Mali and buy myself a djembe. I knew it. And here I was!

On the outskirts of the city the car pulled to the side of the dusty road where a few men busied themselves carving wood and stretching skins. Though I could see no shop per se, this (we were told) was the best “music store” in Bamako. As I approached the proprietors I was tingling with excitement.

I greeted the drum makers and asked if I might try out their wares. I was told that they could make something custom for me but I told them no, I wanted to try out the djembes they had that were already made. I had to hear them.

The men hurriedly assembled a handful of drums that were scattered about and I went down the line: Boom Dun Din and on to the next. Boom Dun Din, Boom Dun Din…

Finished, I stood there scrutinizing and scratching my chin when lo, from out of nowhere one of the craftsmen appeared with another drum which he set in front of me.

I tipped it slightly and brought my hand down three times…BOOM! DUN! DIN!

The damn thing sounded like thunder.

“I’ll take this one,” I gasped. After a brief negotiation I paid them $100US plus an additional $10 for a fabric carrying bag, which they would arrange to be made for me right away. I was concerned that the goatskin drum head might make it difficult to bring back to Canada but I decided to burn that bridge when I came to it. On Baba’s suggestion I decided to leave the drum with them and pick it up just before we departed the country. With my backpack and guitar I already had plenty to lug around.

By this time m’lady and I were beyond starving, so our next stop was for lunch at a nearby restaurant. It was dark inside as we took a booth and pored over the thin, photocopied menu. We both ordered rice that came topped with a delicious onion sauce but even my manic appetite couldn’t help me empty my bowl. As the lady took away my leftovers I heard childhood echoes of my mother admonishing me to finish my dinner because there were thousands of kids in Africa who would love to have it. I washed down my guilt with a large beer and then we headed to the market.

Bamako has a population of approximately two million and I’d swear they were all at the market. The place was nothing short of chaotic. We crushed through throngs of people crowded around booths that were piled high with every product imaginable. We weaved past ladies balancing overloaded baskets on their heads and around squawking piles of bound-up chickens while eager merchants tried to thrust random items directly into our hands. The atmosphere was so thick that it was impossible to tell when we were indoors or outside or where exactly we had entered or left buildings, as we did over and over. When we passed through the fetish market we saw dried monkey heads arranged in rows and baskets laden with colourful dead birds, along with anything else one might require to keep their spirit world appeased and at bay.

Eventually we ended up back at the same restaurant again, where we drank beers and haggled with our posse until nightfall. Against our better judgement and with some misgivings m’lady and I agreed to prebook a few things through Baba, but given the relatively short duration of our trip and the clear unreliability of local transport we felt it prudent to do so.

Back at the hotel we hammered out the final deal and handed half of all of our money to Baba, in an arrangement which should take care of much of what we hoped to get done during our stay in the country. Then to celebrate/commiserate m’lady and I went out and hit the little string of bars along our “street” for more beers and some dinner.

With bus tickets secured for the following morning and a subsequent alarm setting of 5:40am, we were just finishing up our “final” drinks before going back to the hotel when some young men sat at our booth. We got to talking and they told us of two live shows going on at that very moment, both of them for free. They said that one of the shows was within easy walking distance and they could take us there, so we finished our bottles and followed our new leaders.

Five minutes later we were at the Palais des Arts, a fairly large building that hosts concerts and theatre productions. Around the back was an outdoor area called the Cafe des Arts* where a band called Mondank was kicking it down before an audience of perhaps thirty people. The band consisted of electric guitar, bass, djembe, drum kit, gori (like a smaller kora**), and a vocalist. They played all-original music that just seeped that wonderful, unmistakeable West African sound that pleases my soul so much. As the band weaved thousands of hypnotically repeating notes around just one or two chords the vocalist overlaid ethereal, seemingly unconnected melodies through big, overdriven speakers that lent a cackling authenticity to the overall sound.

Several ladies were dancing when we walked in and soon three or four men joined the dancefloor. Without a word or any discernible signal they all started dancing in choreographed unison as if we were an audience to some well-rehearsed, low-budget music video. It was surprising and deeply entertaining.

After a couple of hours and several rounds bought by yours truly our young hosts started trying to sell us things, and they quickly got aggressive. When they had asked what I did for a living back in Canada I’d lied and told them that I was a boxing instructor, which may or may not have encouraged them to back off when I stood up and gave one of the guys a loud, emphatic, chest-poking “NO!” We took this as our cue to get ourselves back to the hotel, which is exactly what we did. It was around 1am when we finally hit the sack in our positively sweltering room.

My goodness, there is so much I’m leaving out about the day, but one can only type so many words.

*At the entrance of the venue I noticed a poster advertising an upcoming concert featuring a band called Farty. I bet they stink.

**The kora is a West African harp-like instrument with a gourd and about thirty unfretted strings. The living master of the kora is Toumani Diabaté. Do yourself a favour and find him on youtube.

111208 The Trip to Mopti

When my alarm sounded well before 6am I was jarred from a deep dream while m’lady didn’t wake up at all; she hadn’t slept in the first place. Despite several nighttime showers the heat had kept her awake the entire night. That’s what we get for not paying to use the air-conditioner.

I dragged my carcass out from under the mosquito net and took a shower myself. Though by this time I had been showering exclusively in cold water for more than fifteen years, the frigid water was still quite shocking and painful. It’s probably because I was already sweating bullets, 80% due to the heat of the coming day and 20% due to all the alcohol I soaked up the previous night.

But we’re troupers: early as it was we were outside waiting for our ride right on time. I don’t know how long it took us to decide that our pre-arranged taxi wasn’t, but eventually we walked to the main road to flag a cab and we got ourselves to the bus station.

By 7am we were onboard our bus and settled in for a ten-hour journey to Mopti. It was certainly no Greyhound and it had no bathroom but it was surprisingly comfortable. I was expecting the bus to be a standing-room-only packed-to-the-roof scenario and I was pleasantly surprised to be surprised that it wasn’t. As we sat there waiting to depart our man Baba showed up as he said he would, stepping onto our bus and greeting us with a wide smile. He gave us several envelopes to deliver to his contact in Mopti and assured us that we would see him later. His arrival at the bus depot greatly eased my not-so-slight concern that we had been shafted out of half of our money the night before. Phew!

Our bus left when it became full. Aside from us there were four other foreigners aboard. Unfortunately, in addition to being sleep-deprived m’lady was also feeling quite ill, so she spent the whole ride trying her best not to vomit. Not only did she succeed, she was characteristically very strong and stoic about it.

Like the bus, the road was in surprisingly good shape, and we progressed at an admiral clip. The view outside the window was reminiscent of a CARE infomercial. Scraggly trees and patches of grass grew out of the dirt dividing one mud-brick village from another. Whether driving cattle, herding goats, or sitting beside the road absent-mindedly swatting flies away from buckets of fruit for sale, everywhere I looked I saw people working hard to make their way through the sweltering day. The bus would stop periodically, each time setting off a flurry of women who clamoured towards the bus carrying baskets of food, drinks, and other things to sell to the passengers. During one such stop a man rode by on a bicycle with a live goat strapped to the back, a sight that seemed utterly unremarkable to everyone but us. I noticed one solar panel amongst the entirety of the seemingly otherwise unpowered villages, and that single panel was accompanied by a prominent sign advertising the agency that had supplied it.

Sporadically napping throughout the long, dusty journey, at one point I was lulled awake by a tiny tapping on my knee. I opened my eyes to find the cutest little girl staring up at me, no more than two years old. When she saw that she had gotten my attention she broke into a huge smile. I couldn’t help but to smile back. We made faces at each other and laughed for a minute or two until her father noticed that she was missing. He got up and walked down the aisle with a smile of his own, returning to his seat with his daughter and parking her on his lap. As I stared after them I was forced to recall a haunting statistic from an article I’d read on the plane: 50% of children born in Mali won’t live to see their fifth birthday. My sleepy grin disappeared and I turned my attention back to the window.

The terrain remained flat, prairie-flat, with baobab trees and termite mounds poking up from the horizon. It was dusty, arid, and very, very hot, with nary a cloud in the sky. I was forced to wonder how the trees could possibly appear so lush.

Again the bus stopped aside another village, again more women rushed to ply their wares. A couple of times throughout the day the men got off with their small mats and they all knelt in the shade of the bus to pray. Every element of the journey was fascinating and relatively comfortable; there’s no better way to see a country than travelling the same way the locals do.

After nine-and-a-half hours on the bus we finally arrived in Mopti (the fare cost 8,000 each, which was less than $20CDN). Somewhere along the way m’lady had started feeling better and otherwise the ride had been relatively painless, but when we stepped off that bus and into the mayhem that accompanies arriving busses in these parts we were hot, tired and hungry. Especially “hot”.

So we were very happy to immediately meet our contact and climb into his 4×4 for a relaxed, worry-free ride to our hotel. As we checked in we were happy to find a nicely decorated, clean lobby and equally pleased with our room for just 13,000. When the proprietor showed us the hotel swimming pool I bolted towards the water, fully clothed. The hotel guy reached out and casually held me back, cartoon-style, as if this sort of thing happens all the time. Good thing too: I was still wearing my backpack.

Okay, that might not be entirely true but this is: It took less than two minutes for me to get suited up and dive into that pool, and it was absolutely glorious. Numb with joy and blissful appeasement I ordered a couple of poolside beers and made small talk with a few other travellers. After a bit of asking around I was consoled to learn that we seemed to have bargained an excellent price on the stuff that we had pre-booked with Baba. That called for another round! By 7pm m’lady and I mustered our final stores of energy to climb up to the hotel’s rooftop restaurant where we really, really enjoyed our first and only meal of the day beneath a monstrously large full moon.

The extreme heat and the lingering dregs of jet-lag settled into the magically foreign surroundings and forced a backdrop of surrealism to the evening. The fact that we spent dinner discussing our pending camel-trek to Timbuktu made it even more so.

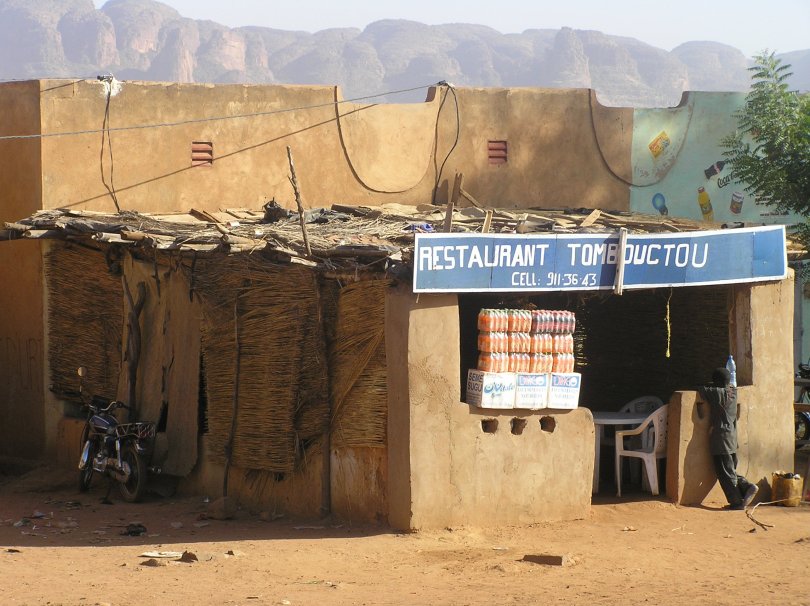

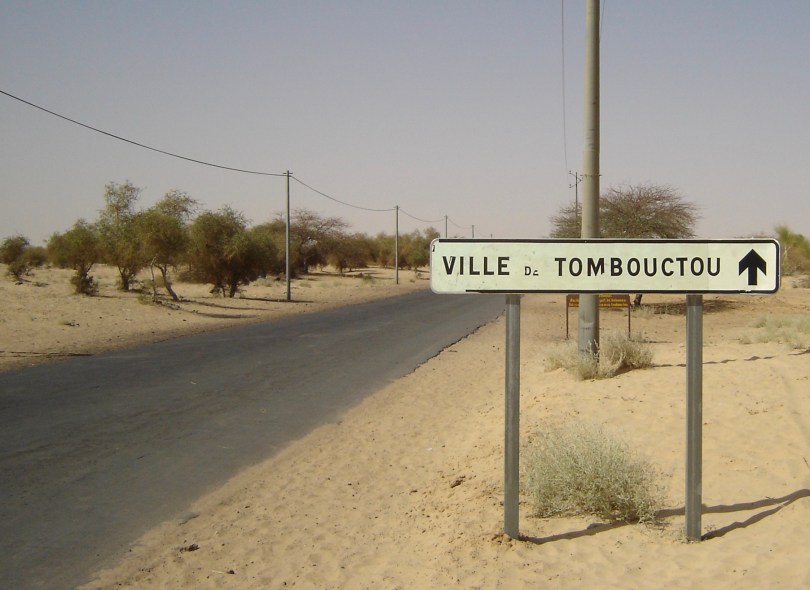

111308 Timbuktu

M’lady had more sleep to catch up on than I did, so while she headed to our room right after dinner the previous night for some well-needed shuteye, I kept myself busy drinking beers and playing guitar on the terrace. I quickly discovered that my only common ground with the locals seemed to be Bob Marley, so I played every Marley song I could think of until they closed the bar at the ridiculously early hour of 11pm. Even still, it felt like my alarm clock’s morning interruption at 5:45am came much, much too soon. Again. This was becoming an unfortunate habit.

At 6am we were outside, squinting under the unimpeded sun. In short order were joined by another yawning, stretching, squinting tourist, a stocky Englishman about my age with a round face and a thin smile. British Steve was another client of our man Baba, and he would be joining us for our coming adventure. After the briefest of small talk our driver arrived. Handshakes and introductions all around, we tossed our gear in the back of his 4×4 and the four of us set off for a long day of driving.

As we left Mopti our non-Jeep jeep remained on a smooth ribbon of asphalt that became increasingly encompassed on both sides by an infinity of near-emptiness. After an hour the road started to morph into a rough dirt track and eventually it vanished altogether, swallowed up by the encroaching desert. After that it was mostly just straight-up bush driving. The ride was fast, long, jarring, and simply unbelievable. The main purpose of wearing the seatbelt seemed to be to keep our heads from repeatedly bouncing off the roof of the jeep. Despite this I almost chipped a tooth a few times.

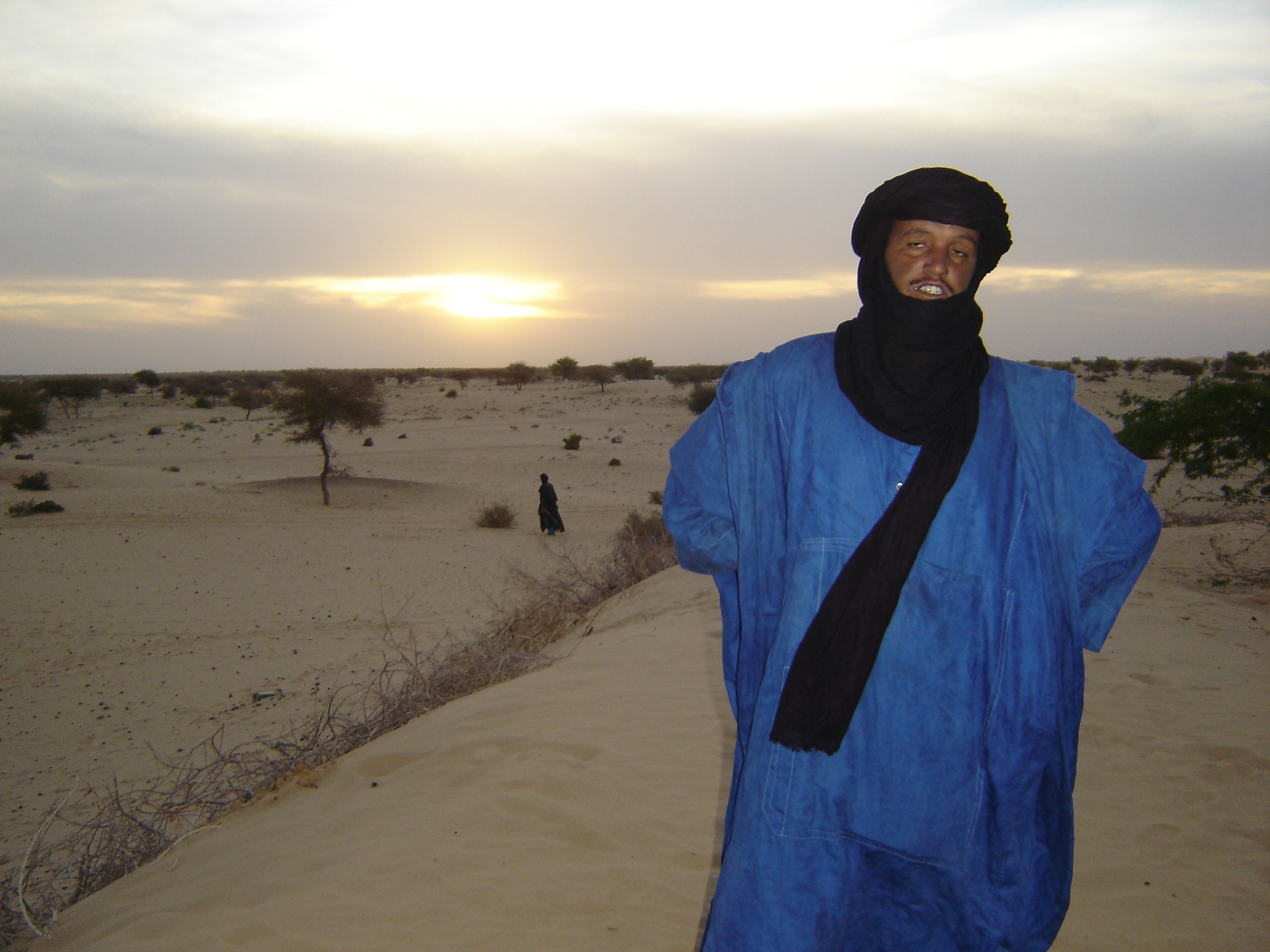

We drove past village after village, ageless pockets of life where herding goats and pestling grain seemed to be the chief concerns. In the ever-widening landscapes between the villages camels driven by Tuareg nomads dressed in blue robes and turbans became commonplace. The scenery was constantly sublime and the experience unforgettable.

After seven hours we arrived at the shores of the Niger River. While we waited for the ferry I played with a group of children that surrounded the dock. We amused ourselves by finger-painting portraits of one another into the dust-caked body of the 4×4. Meanwhile an impromptu game of hacky-sack broke out, but of course nobody actually had a hacky-sack. The game began with some sort of unidentified fruit peel in place of a real ball before upgrading to an empty cigarette pack.

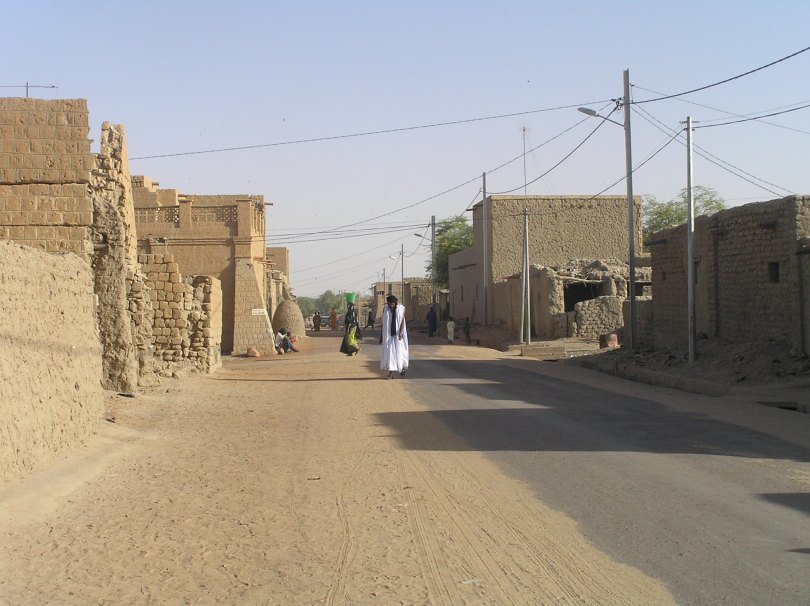

When the ferry arrived it filled up immediately with the three waiting vehicles, a dozen people, one cow, two goats, and countless chickens. And with a swarming goodbye wave from the kids we were off. When we landed on the other side we were in Timbuktu county. Twenty kilometres later we entered the fabled but quite real city of Timbuktu. We checked into our Baba-booked hotel and headed out for a walkabout and hopefully to find some lunch.

Timbuktu was established approximately a thousand years ago by the desert-dwelling Tuareg people. The city changed hands several times as it grew to become a major trading centre. Due to its location on the fringe of the Sahara Desert and proximity to the Niger River the city became a hotbed of the salt trade, which it still is. And you remember that old saying about something being “worth its salt,” right? Well, that came about because salt used to be an extremely valuable resource. Throw in a little bit of gold, ivory, and slave trading and the desert metropolis of Timbuktu quickly grew to legendary status. A major university was founded there, as was one of the world’s great libraries.

Where there is wealth there is bound to be strife, and for a multitude of reasons Timbuktu eventually skid into decline. At one point the city was burned to the ground, library and all, and after a quick walk along the dusty streets I must admit that it appears that Timbuktu didn’t bother to do much rebuilding after the fire. Little seems to remain that is worthy of attracting weary travellers from the world over, aside from the city’s wonderfully exotic name, of course. Well, that and the flinching awareness that one has reached a locale that many explorers lost their lives trying to get to not so much as a hundred years ago.

As a pair of conspicuously white tourists, m’lady and I attracted quite a bit of attention during our stroll. We were never not being greeted, followed, and fawned upon. After an obstacle-laden wander through the market and a few pictures of the big, beautiful mud mosque in the middle of the city m’lady tired of the nonstop interaction and decided she was ready to go back to the hotel. On the way we passed a radio station and I poked my head in for a quick peek. The primitive equipment gave the station a range of only about a hundred kilometres, but for the people within that radius the station provided an indispensable source of information and connection.

Back at the room I grabbed my guitar and went outside to continue exploring on my own. I emerged from our dwelling with the guitar strapped to my back Springsteen-style and made it about two feet before a Tuareg man insisted that I follow him, as his father was the greatest Tuareg musician in all of the Sahara. A short walk back through the market brought us to his family’s house. Or rather, the tent that they had temporarily pitched in the front yard of someone else’s house. Nomads, remember?

It turned out that the guy’s father wasn’t home so with a shrug he pulled a satchel of jewelry out from beneath his robe and started trying to sell me stuff. I had only been in the city for a few hours but I already knew that the Tuareg people were well known for both their fine silver jewelry and for their overly-aggressive sales pitches, so I immediately left.

A block away a group of Tuaregs asked me to play for them so I did. In no time we were surrounded by dozens of people, all of them clapping and dancing. Eventually I moved on but wherever I went I recreated the same scene. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that wherever I went I caused a scene. Walking around Timbuktu with a guitar made me feel like I was fifty feet tall.

One young man coaxed me to follow him to his family’s house. I explained that I’d be happy to but made it clear that I didn’t want to buy anything. He said it wouldn’t be a problem because he was not a jewelry maker like the rest of his tribe. He told me that he was a student and that instead of making jewelry he wanted to become a musician. I said “Okay,” and followed him home.

Along the way we were stopped by two goats who became engaged in a devastating head-butt fight. The street was immediately made unpassable as everyone gathered to watch, just like kids inevitably surround a schoolyard scuffle. And really, if a guy like me pounding out squawky Bob Marley covers counts as entertainment around these parts then of course a solid round or two of unhinged goat violence is going to pull a crowd.

Facing each other with their heads down, the goats would scratch the dirt in front of them like angry bulls before crashing headlong into one another with astounding speed, incredible strength, and brutal force. Whack!!! I was amazed that either creature could survive even one attack, and they went at each other at least ten, maybe a dozen times! Finally one of the goats faltered and staggered away and the street returned to its usual dusty bustle. My new friend and I continued on to his house.

When we arrived I discovered that, just like my last host, his family’s home consisted of a yurt that was set up in front of another family’s house. My new friend went inside and brought out a blanket to lay on the ground. We doffed our sandals, he grabbed his “guitar” and we sat down and played together.

His was the traditional instrument of his people. I can’t remember what he called it but I suppose it could be described as a primitive mandolin or perhaps a small banjo. It had a small gourd-shaped body made of wood with a top of stretched animal skin and a fretless neck that was reminiscent of a sawed-off broomstick. The instruments’s three nylon strings were permanently fixed, there were no tuning pegs at all. I twisted my highest strings to approximate his and when I managed to copy some of his motifs he was thrilled.

With an instrument that was utterly untunable, the man’s playing focused on rhythm rather than tonality, something that was highlighted to me when we switched instruments. When he corrected my playing it was always about the rhythm. He ignored the notes I was playing altogether.

Eventually he handed back my guitar and asked me to play him some blues music. I did, making up the desert blues as I went along (“Got the desert blues/Got the sand in my shoes/Got the desert blues/And I’m stuck in Timbuktu”). His entire extended family suddenly emerged from the tent, dancing and clapping and obviously very pleased to have me there. I found the reaction kind of surprising because aside from Ali Farke Touré I had yet to hear anything like blues so far – only traditional Malian music and reggae – but it sure was great to see the whole family having so much fun. I was also surprised because I’d had no idea that there had been anyone inside the tent.

By this time the sun had gone down so I soon begged off and circled my way back to the hotel, where I found m’lady mercifully still asleep. I went to the restaurant and spiked a few Cokes with little airplane bottles of whiskey that I had brought from Canada. I whiled the time chatting with the only other patron in the joint – a British tourist who wasn’t Steve – the two of us repelling random Tuareg sales pitches the whole time. When I ran out of teensy Canadian Clubs I switched over to local beers. When I ran out of company I pulled out my little alphasmart word processor and did some typing. Eventually the lone barman closed the place and left me all alone.

Swatting drunkenly at malarial mosquitoes and staring up at the vast canopy of stars it occurred to me that along with the steady chirping of sand crickets I could hear drums beating in the distance. And while I should have been thinking about nothing but bed, I just had to find out where that music was coming from.

111408 A Big Day in the Desert

Before turning in I had staggered back and forth through the streets of Timbuktu following the sound of drums. The doppler effect created a musical mirage that tricked me into chasing the ricocheting rhythms as they bounced up one street and down another, until suddenly the drumming stopped. Before embarking on my sonic search I’d stopped into the hotel room and emptied my pockets of all valuables and money save enough to buy one beer (I may be crazy but I’m not stupid). Suddenly left with no music to wander towards I decided to find somewhere to have that last beer.

The streets of Timbuktu are surprisingly busy at night, but after stopping at a few establishments and finding no beers for sale I decided it was perhaps most prudent to get my drunken ass back to the hotel. I didn’t think that I was very tired but once I fell into bed I was asleep in seconds.

M’lady’s morning stirring roused me from my slumber and we decided to go for a walkabout before it got too hot outside. We aimed north, weaving slowly along the side streets watching Timbuktu’s morning unfold. It felt distinctly like strolling through Mos Isley, but without the Imperial Stormtroopers.

We eventually walked our way right out of town and found ourselves standing in the Sahara Desert. Turning around we zigzagged our way back through the city until we came across the Flame Of Peace Monument, where about a dozen children sat, seemingly waiting for us. “Shouldn’t you kids be in school?” I asked. En masse they pointed at just one member of their crew, “Yes, he’s supposed to be in school!”

For centuries this area was the exclusive stomping grounds of the Tuareg people, nomads who wandered unfettered throughout the vast desert in pursuit of the lucrative salt trade. When nationhood grew out of the African independence movement of the 1960’s geopolitical boundaries suddenly appeared, disrupting historic trade routes and restricting the movements of the Tuareg people, who were exiled to neighbouring countries including Libya and Algeria. To the Tuareg these national borders were nothing more than imaginary lines drawn in the sand. They began to revolt, demanding a large swath of the Sahara that they could call their own.

After decades of fighting Malian president Amadou Toumani Touré brokered a peace deal (which did not include handing over any land to the Tuareg) and in 1996 ten thousand people gathered in Timbuktu – on the very spot where we were standing – and handed over their weapons to be destroyed. In total more than three thousand guns from both sides of the conflict were burned that day. To honour the agreement, a monument was built from the remains of the scorched and melted pile of firearms, and while the sculpture is relatively unremarkable in size the significance of what the memorial represents to the Saharan people is enormous.

After a short visit m’lady and I decided to continue our stroll. leaving the kids to jump and play on the Flame Of Peace like it were a set of playground monkey bars. Along the way I heard some crazy music wailing out of a building and poked my head in. I was surprised to discover that the main instrument I heard was actually a recording, an electric guitar or something similar that was being beautifully distorted by squelching much too loudly out of a tiny speaker that was barely up to the job. Next to the speaker sat a man who drummed along on a gourd of some kind. It turned out I had interrupted a wedding rehearsal. The groom – dressed all in white and looking like a prince – greeted and welcomed me while the women invited me to join their dance. Of course I did, much to their amusement and mine.

Back out on the sunny street m’lady and I decided that we were at least half-starved so we kept an eye out for somewhere that we could get some breakfast. We found an establishment that seemed up to the task and sat at one of their half-dozen tables, the only customers in the place. When we asked for a menu we were brought a weathered piece of paper with Arabic writing on it. We pointed at splotches of ink and were told what each item was. None of it sounded very breakfast-y but most of it sounded pretty good. By this time we were all-the-way starved and we might have said “yes” to a few more dishes than perhaps we needed to. Suffice to say, when we finished ordering I felt like we might have overdone it a little, like when you order a plate or two too many at a Chinese restaurant.

It took at least a half-hour for our first dish to arrive, and when it did I was flummoxed. The man brought out an enormous bowl full of millet and chicken and simply set it on our table. I mean this bowl was at least a good two, maybe two-and-a-half feet across. “What’s going on?” I wondered aloud. “This can’t all be for us…”

The man stood back with a smile, nodding and encouraging us to begin eating.

“Oh no! This means…”

And sure enough, when the beef and rice came out it was also enough to feed a dozen people. Same for the salad and the sides of vegetables. Our waiter soon pulled another table over to ours so he had room for everything. Our order of bread amounted to a full loaf. When all was said and done we had ordered enough food for twenty or more people. By the time we had eaten our fill we hadn’t put even the slightest noticeable dent in the massive spread.

Our bill still came to an absurdly low amount and by the time we settled up we remained the only customers in the restaurant. I gestured to the empty tables and asked the proprietor with a shrug why nobody else was there and he pointed to a small clock, indicating that 9:30 was too early for customers.

9:30? M’lady and I looked at each other in shock. “It’s only 9:30?!?!” We thought it was noon or 1pm at least! We had been in the restaurant for probably close to two hours, and before that was the kids and the wedding party, plus all that walking around. We just assumed that we had woken up around 7:00 or 7:30 but it turns out we had accidentally been out romping through the streets since well before 6:00am, probably closer to 5am. Here we were fed full to the elbows and it wasn’t yet ten o’clock. Talk about getting a jump on the day!

We walked off our “breakfast” by looking for and finding the post office, where I sent myself a couple of postcards. We paused beside a school and listened to a class that was being held outside in the school’s dusty courtyard. The students responded in unison to the teacher’s every question. The teacher started leading them through the English alphabet and I was pleased to hear that they ended with “zed” and not “zee”, just like we do in Canada. During their second recitation I stuck my head over the fence and joined in, which caused the young children to explode into riotous screaming and jumping around. I ducked away and left the teacher scrambling for order, then we booted it back to our hotel.

Along the way we passed a cemetery, just the second we’d seen in Mali so far. Both looked like little more than rubble-strewn patches of rough earth, each dotted with a number of small, hand-painted signs. The wooden markers were so simple and plainly written that one could easily mistake them for advertising a garage sale or something equally mundane rather than marking the final resting place of someone’s dearly departed.

I don’t know why I find graveyards so interesting, but I sure do.

Back at the hotel we relaxed in the open-air bar, sipping cool beers in the shade and watching the city around us roast. Despite the oppressive heat the locals still found it chilly, many of them walking under the noonday sun wearing multiple layers. Some walked by wearing winter jackets zipped all the way closed, just like Kenny in South Park.

To think that people even have winter jackets in Timbuktu. But then, what do I know about riding camels through the Sahara Desert and sleeping on the barren sand?

Not much, admittedly. But I was about to find out.

Now, if you’ve been keeping track you’ll notice that it’s not even lunchtime and m’lady and I are gearing up to ride camels into the desert to spend the evening with the nomads. And yet with a missive already this massive I feel it prudent, dear friends and readers, to pause for reflection before I continue with the adventure, lest the reading of this diatribe take up too much of your day. So let us suspend the action here and freeze on this moment in which m’lady and I lounge in the shade with drinks and watch the world go by.

Until next time.

INTERMISSION

The interested reader may recall that before I calved the tale of this day in half m’lady and I had already spent 6+ hours exploring the glaring, blaring streets in and around Timbuktu before the hour had even struck noon. At last word we were resting easy in the hotel bar as the world unfolded around us. The remainder of our day had been preplanned and prebooked back in Bamako through our man Baba and all we had left to do was be ready. And so we readied ourselves with a steady stream of cool drinks and lazy relaxation.

It was late late afternoon by the time we were summoned. Behind the hotel we found British Steve, whom we’d met the day before when we shared a jeep from Mopti to Timbuktu, and together the three of us met our Tuareg guide Mama, his assistant, and their three camels.

When m’lady and I had haggled our bookings with Baba he’d recommended we take a camel journey into the Sahara and spend the night in a traditional a nomad encampment. We waffled while he insisted that this was a must-see if we were to be in Timbuktu, and we were. After a little more humming and hawing he dropped the price down so far that we felt we would probably spend more more money just sitting around doing nothing for a day. So we booked it.

The three camels were for British Steve, m’lady and I to ride while Mama and his assistant would walk ahead, leading us. The men coaxed the camels to their knees and the three of us mounted our lumpy steeds. We rode on the camel’s hump in saddles that sported a tall wooden plank up front where a saddle horn would traditionally be. As my charge clamoured up to a standing position I hung on to that plank for dear life. M’lady and British Steve did the same.

And then we rode our camels out of Timbuktu and into the vast Sahara. Crazy.

Mama and his buddy led us about six kilometres into the desert, both men holding a cellphone in one hand and a camel’s reins in the other. When I first saw these two robed and weathered desert nomads carrying their modern cellphones I was taken aback, but it quickly struck me: who needs a cellular telephone more than a nomad?

(Speaking of cellphones, partway through the afternoon ride British Steve had to dig into his backpack to answer his cellphone. It was a work call and he quickly begged off, explaining that he was actually a bit busy right now riding a camel through the Sahara Desert and could they please call back next week? I wondered if the person on the other end of the line could possibly have believed him.)

Though there was no mistaking the barren fact that we were in a desert, I was surprised how dotted the landscape was with vegetation, rough as it was. Rather than Tatooine-like hills of empty sand retreating into the horizon as Hollywood would have it, the endless dunes were scattered with scraggly trees and thorny bushes that looked like rooted tumbleweeds. Speaking of Tatooine, we passed quite a few wells along the way, round concrete structures that would fit right in on the Lars family homestead. When I inquired with Mama he invariably described each well by the nationality of the volunteers who built it. “That is a German well”, “This one is British”, “This one was made by the Dutch…”

The ride was somewhat uncomfortable but things could’ve been worse; at least I wasn’t the camel. Though to be honest, Mel didn’t seem to mind. And no wonder; camels are larger and heavier than horses and they have evolved themselves to be very well-adapted for slow, steady progress. (Yes, I named my camel “Mel”. I wasn’t about to go riding through the desert on an ungulate with no name. M’lady named hers “Cammie”.)

And so it was that after a slow and steady hour or so we arrived at a small Tuareg outpost that consisted of three tents and a firepit widely surrounded by a ring of thorned bushes. We were shown our quarters, which were spartan even compared to where the Tuaregs slept. Whilst they stayed in sizeable yurts, we would be sleeping on a mat lying on the open sand with just a single curved rattan wall set up along one side to serve as a windbreaker. There were large beetles running all over the ground making cute little tracks in the sand and burying themselves in preparation for the long, chilly night. It seemed like the beetles were happy to steer clear of us so they were a-okay with me.

The sun went down not long after we arrived and soon it became very dark. Our guy Mama approached from the yurts carrying a large, steaming bowl. His assistant handed everyone a wooden spoon and the five of us sat in a circle around the large bowl, collectively digging in to our shared stew of some nameless meat, rice, and gravy, which was liberally peppered with crunchy Saharan sand. For our desert dessert Mama cleaved up a large oblong watermelon.

After dinner came the inevitable sales pitch. Mama and his friend began laying several pieces of cloth on the sand and set upon them countless handmade silver necklaces and bracelets. Most of these were formed into Tuareg “passports”; flat plates of silver that were clipped and cut into designs representing different regions within the vast Sahara, shapes that were recognizable only to the Tuaregs themselves. As they set out their wares Mama explained that if we saw anything we liked we should take it from their mat and put it on our own, and when all the selections were made the bargaining would begin. And indeed, they had laid an empty mat out before each of us.

Unspoken but obvious was the fact that if you put something on your mat you would definitely not be leaving without it, bargaining bedamned. We had heard of the Tuareg style of bartering; they make one offer, you make a counter-offer. They make a second offer and so do you, and then each party has just one more chance; it was during the third offer that the final price would invariably be settled (“The first offer is strong like death, the second is sweet like life, and the final offer is sugary like love”). Or so they say.

British Steve and I adamantly ignored any and all items pushed towards us, leaving m’lady to suffer the entire brunt of the aggressive sales pitch alone. While the two of us looked on m’lady tentatively placed a bracelet and a necklace on her mat. Three back-and-forth bids were made but no common ground was found. And whattya know? The men went on to counter with a fourth, fifth, and sixth offer, and then some. So much for the Tuareg bartering style, thought I.

But then, when it seemed like no price was going to be agreed upon Mama sighed and wordlessly unsheathed the menacingly large dagger that perpetually dangled from his side. He held it up and looked at it briefly before plunging it suddenly into the sand beside his mat. He then lifted his eyes and stared at m’lady, thickening the sudden, uncomfortable silence. Running his hand over the two item like a model on The Price Is Right, Mama calmly restated his third offer. M’lady followed up by repeating her third rebuttal. After a brief pause Mama pulled his dagger from the sand and sheathed it, agreeing to m’lady’s price. Sugary like love? It didn’t look like it. But under the circumstances, I thought as Mama and his pal left us to return to their yurts, I think we did pretty darn well.

Before long about a half-dozen children came over to meet us, bringing with them a pair of impossibly small kittens that couldn’t have been two weeks old. The night had started to get chilly and m’lady busied herself coddling the kittens to keep them warm. Meanwhile I pulled out my handheld tape recorder and pressed the record button.

Three little girls ranging in age from around three- to nine-years old sang a stream of songs for me. Each melody was simply beautiful, reminding me alternatively of Indian music, Inuit throat-singing, or old pre-Blues field hollers. The music was tonal and full of inflection, and the singing was really impressive. After every song I rewound the tape and the girls sat enthralled, shushing everyone and listening intently. Once the playback ended they would rush to sing another, and with the final note they would clamour at the recorder insisting that I play it back. Soon all the kids wanted in on the action and the quiet trios gave way to group sing-alongs, with the boys (of course) eventually crescendoing to screaming, cacaphonic noise. Eventually I feigned dead batteries; the kids went to bed and so did we.

I offered m’lady and British Steve each a nightcap of tequila shots and I was so shocked to get no takers that I decided to abstain myself. With a nearly full moon reflecting brightly off the desert sand and only the occasional goat bleat and camel fart to disturb us, we three settled into the surprisingly hard ground, laid our heads on our stiff wicker pillows and tried to sleep, with m’lady still coddling those two tiny cats.

At some point during the night the three of us were awoken by a camel who noisily trotted by* not more than a metre or two away. We all sat up with a start, blinking back-and-forth at each other in sleepy astonishment before settling back into the hard-packed sand. As my gaze returned to the impossibly starry Saharan sky I tried hard to convince myself that I wasn’t dreaming. I suspect the others were doing the same.

*At night the Tuaregs leave their camels untethered, instead attaching a length of wood between their two front hooves. This hobbles the animal, reducing its mobility to short lurches and leaps and preventing it from escape.

111508 Camels, Trucks, and Boats

Neither m’lady nor I slept very well, for a lot of very good reasons. First of all, sleeping out in the open on a woven mat laid directly on the hardened Sahara sand ain’t no Club Med (thank goodness). Secondly, m’lady had to do a lot of tossing and turning to keep her new kitten friends warm and safe from squishing throughout the night, actions which helped to keep me awake. In the tiny pockets where I did manage to fall asleep my snoring would wake her up in turn. And so it went.

It was probably sometime around 4am when I tossed and/or turned for the last time of the night. I figured one of us might as well get some shuteye so I got up and waited for the sun to rise. I parked myself on the fringe of the small nomad camp and listened as the desert world slowly came to life around me. The camels and goats predicted the pending morning with increased bleating and snorting and eventually I was treated to a pretty Saharan sunrise.

In the dim morning light I silently watched as two women emerged from their yurts to start their daily chores. Moving silently through the din in their dark head-to-toe robes they looked for all the world like a pair of stealthy ninjas preparing a stealthy ninja breakfast.

When the sun came all the way up everyone in the camp started to stir. Our Tuareg host Mama and his friend busied themselves filling up the camels, a chore that amazed me. You know that saying, “You can lead a horse to water…”? Well, that doesn’t apply to Tuareg camels! Going down the line, one man would tip back the head of each kneeling animal and hold its mouth open with both hands while the other man tipped a watering can deep into the creature’s mouth. No surprise: the camels didn’t like it one bit. The inevitable braying gave way to gurgling grunts as each camel’s “tank” was filled, and the procedure was repeated three or four times on every animal. Once each of the protesting animals had several gallons poured into them we were ready to mount up for our ride back to Timbuktu.

It wasn’t until we neared the city that I finally started getting comfortable sitting in the odd saddle and cupping my feet together to maintain balance, and the next thing I knew we got dropped off at our hotel. We went inside and immediately gathered up our things, checked out, and hopped into a waiting truck to be driven to the banks of the Niger River.

There were a few kids scattered around as we waited for the next leg of our journey to commence and pretty soon they started asking us for stuff. I am loath to give handouts, especially to kids, so instead I pulled out my guitar. Dozens of little tykes appeared out of nowhere and I was quickly swarmed. For the next hour or so I bounced between playing for them and giving them all a try at strumming the instrument themselves. Meanwhile m’lady attracted a swarm of her own as a half-dozen girls started playing with and ultimately braiding her hair. Eventually our boat arrived and the two of us along with an older Dutch couple named Johann and Ritt joined a crew of three and together we all set of on a three-day river journey back to Mopti aboard a long, thin vessel they referred to as a “pinnace”, which could easily seat fifteen passengers plus crew.

(Following pre-emptive apologies to m’lady and I, Johann and Ritt began the adventure with an extensive argument with the boat’s captain, insisting that they had paid extra for a private boat. They ultimately lost their fight and with embarrassed smiles to us we were welcomed aboard.)

About forty-five feet long and no more than seven feet wide, the pinnace was fitted with a pair of standard outboard motors lowered through a hole near the back. The boat featured a few thin benches covered by an awning, a table for eating, a cooking area, and a bathroom behind the engines that was nothing more than four short walls flanking a hole cut through the floorboards to the water. To maneuver around the vessel one needed to scuttle along a six-inch wide gunnel that circled the outside of the boat on all sides.

Though the pinnace was overtly plain, it had everything we needed to enjoy a lazy meandering trek upriver. Most specifically the boat offered unimpeded views of the villages and the people who inevitably appeared on the banks to wave as we puttered by. And while the views were continually amazing, astounding, and inspiring, I felt an enduring hankering to enjoy it all with an ice-cold beer in my hand. Unfortunately this was a feature that the boat was seriously lacking.

Wondering how I was expected to wash down my stash of tequila, with an hour left of sunlight we found ourselves floating past the city of Djiri. On my request the boat pulled in to the bank where men and boys were socializing, washing clothes and bathing. M’lady seemed happy to stay onboard while I bounded onshore to find a bar or something close. I soon met with success and returned with a cache of hot beer and ice, and once I combined these things with a cooler and a little out-of-character patience I was treated with quite a treat.

Our morning departure had come later than expected so we had to travel a couple of extra hours after sunset to arrive at our first camping spot. By the time we arrived I had treated myself so well that I promptly fell off the gangplank and into the water with no harm done. As our crew got busy setting up tents for the night we four tourists stood on shore and gaped madly at that glorious spectacle that can be had from nearly every vantage point on this wonderful planet: the Milky Way, which in this instance was made even more spectacular by the powder-like sand coursing between our toes and the now-familiar sound of steady drumming and joyous singing emanating from some nearby village. Eventually we were called back on board for a dinner of rice and bones which eventually gave way to slow, sparse conversation with our travelling companions until it was finally time to sleep.

As I laid down for the night I found it difficult to believe that only a week had gone by since we had landed in Africa.

111608 Niger River Beer Run

When I climbed into our tent to go to sleep it had been warm enough that I doffed my shirt and stripped all the way down to my skivviest of skivvies, but as the night progressed it started getting colder. Eventually it got downright chilly. I put my shirt and pants back on and was soon groping around for more clothes. When our 4:30am wakeup call came I looked like Milton Berle on a bad day. I had put on as many shirts as I could find, I was wearing the detached legs of my convertible pants/shorts on my arms like sleeves, and I had pulled one of m’lady’s dresses up over my head upside-down. I was wearing the dress like it was a pair of pants, with my legs stuck down through the arm-holes.

Under the generous light of a setting moon m’lady and I, along with our two co-travellers Ritt and Johann, were ushered aboard the slender pinnace to begin another day upon the Niger River. As the sun began to rise we were treated to a Lion King view that could only have been a collaboration: the swirling orange and blue water was painted by Van Gogh, the undulating hazy sky was classic Monet, and the sandy, suede-coloured shoreline dotted with surreal huts and bulbous termite mounds was undeniably Dali-esque.

At the risk of being a total cheeseball, I pulled out my guitar and lured the sun out of the horizon with a sleepy instrumental version of Here Comes the Sun. The Dutch couple was kind enough to share their breakfast with us anyway, and I followed up the tasty meal of buttered bread, jam, and cheese with a warm mug of instant Nescafe, so far the only coffee option I had found in Mali. Afterwards there was nothing but to settle in for another day of scanning the river for hippos, waving to the local villagers who invariably crowded the shoreline to greet us as we passed, and idly thumbing through my book. For this leg of the journey I felt it apt to read Joseph Conrad’s Heart Of Darkness for the first time. A good book to be sure, though it made me feel slightly, if appropriately, unhinged. In a good way.

Shortly after breakfast our captain pulled alongside a small boat and haggled for a couple of fish from the fisherman’s catch. As we pulled away our host proudly held up his end of the transaction, a pair of fourteen-inch Nile perch that he announced would be our food for the day. As I pretended to read my book I kept an eye on our captain/chef, and I watched in silent, stone-faced horror as he chopped the fish into large cross-sections and scraped the bloody mélange into a bowl. I’m talking the whole fish, as in everything but the hook; heads, bones, scales, guts…everything. Then he placed the bowl of raw fish up on the roof of our boat and let it sit there to roast/rot in the hot sun for the next hour or two. Meanwhile he had lit some charcoal under a large pot and begun frying up a mix of oil, cabbage, onions, tomato sauce, and a couple of packages of what I suppose were powdered chicken bouillon, along with plenty of salt. Finally he topped it up with water and waited patiently for the mixture to come to a lazy boil.

After what seemed like an immeasurable amount of shore-gazing, book-reading, and people-waving, I watched the captain retrieve his bowl of sunbaked fish bits from the roof and dump the whole thing lock, stock, and entrails into the semi-steaming pot. He ordered the boat ashore at the next village and jumped ashore, quickly returning with a small bag of rice which he boiled on a second charcoal stove. About ninety minutes later our chef announced that lunch was ready.

Now I generally don’t eat anything that comes out of the water (except tuna, which comes out of a can) but I’m usually willing to try a bite of pretty much anything. So willing, in fact, that even after telling m’lady all that I had seen and begging her not to eat any of the fish goo stew I agreed to actually try a spoonful. Otherwise I settled for a few slices of watermelon as my lunch, though to be honest the small taste of stew that I had was much more palatable than I’d expected it to be.

After lunch we finally spotted a couple of hippos. One of the crewmen hollered and pointed so the captain turned our pinnace around and took us in for a better look. The pair of megaherbivores were almost entirely submerged in the river so we could only really get a glimpse of their massive size when they lifted their huge heads out of the water to get some air. I tell you, hippos are big man. Like, I’m talking Volkswagens with legs. They say that hippos are the most dangerous animal in all of Africa with all the people-stomping and boat-flipping*, but it’s hard to believe they’re really so dangerous when one considers how quickly our captain spun our little boat around to chase after them. As if a guide in India would chase down a couple of cobras that slithered by.

Our captain suggested we break up the day with a stop at one of the small villages for a walkabout. We all readily agreed and around the next bend he brought the boat in. The moment we four tourists stepped onshore we were swarmed by smiling children. They crowded around the four of us, all of them reaching to touch us and taking turns shaking our hands. One asked for our autographs. Sure, most of them also called out “Cadeau!’ Cadeau!” hoping to extract some some money or candy from us but none seemed disappointed when we didn’t comply. Certainly no enthusiasm was lost, as the children continued to fight amongst themselves for the privilege of taking us by our hands and leading us all on a tour of their village.

Up close we could see that yes, every building and every structure was indeed constructed entirely of mud: walls, roof and all, impossible as that seemed. The tiny homes were connected by way of narrow walkways that led ultimately to the town’s small mosque. It was all so stark, so simple, so stunning. It was a world apart; at times I felt as though I were being led around another planet.

Back on the boat we were offered leftover stew for supper. I quickly and easily decided to make do with a couple of snack bars, which I munched while casting astonished glances at m’lady for agreeing to eat more undercooked fish parts. To drink I only had a Hankerin, which is another way of saying that I had run out of beer.

After putting in a fifteen-hour day on the river we finally stopped to camp for the night. During the final couple of hours m’lady had started feeling ill. I blamed the stew as diplomatically as I could, but the consensus on the boat was that that she gotten too much sun, which was rather plausible.

For most of the day I had been bugging our captain for an opportunity to make a beer run and finally, as the tents were being pitched he tapped me on the shoulder; this was our chance. The Dutch couple asked for a couple of Cokes if I could find them and m’lady thought a ginger ale might do her stomach some good. I stuffed some cash in my pocket and followed the captain on what was to become a rather epic trek through the quickly darkening jungle. He said there was a village about two kilometres away. “If we walk that way we should find some beer for you.” Soon after we left night fell completely and we pressed on using a flashing red light atop a distant tower as a beacon.

When we had travelled about halfway to the tower we turned abruptly, the captain following a path that was invisible to me. Suddenly I saw a light just ahead of us. It was a lantern no more than ten metres through the brush.

I swear to you, when we stepped into the clearing I could have sworn we had stepped into the Star Wars universe. Standing before me were a couple of worn and weathered concrete igloos that looked exactly like Luke Skywalker’s home on Tatooine. And believe it or not, inside was a cantina, which we found inhabited solely by the bartender.

Amazingly, the place served as a hotel as well, though being the only sign of life within sight and hiding in the brush far from the river with no other means of approach aside from stumbling through the jungle on foot and, well, I can’t see how the place gets much business at all. But it got mine!

They didn’t have any ginger ale so I bought four hot beers and five hot cokes and inquired about ice. The barkeep barked over his shoulder and a young man appeared out of nowhere. The boy told us to follow him, so I gathered up my bounty and off we went.

He led us another kilometre or so, all the way to that flashing red light which turned out to be a transmission tower. Next to the tower was a fifteen-foot satellite dish, a generator, and a tiny hut. Inside the hut we found a man laying on his bunk watching a small black & white television. The only other furniture in the hut was a small deep freezer. It was this man’s job to keep the generator running. As a result, his little hut had a steady supply of reliable electricity, which made him the go-to guy for refrigeration. I paid him for a half-dozen small plastic bags of frozen water and the three of us, and then two, headed back. When the captain and I arrived at the tents m’lady was vomiting heavily and consistently. I wanted to help but could do nothing. I didn’t even have a ginger ale for her. But I must admit, where she didn’t sleep much at all I sure did. I was so spent that I opted to save all my beers and let them cool for the morrow. Then I fell immediately into bed and slept like a dead rock.

*C’mon now. I’m not going to bother looking it up, but I’d bet dollars-to-donuts that mosquitoes kill more Africans than hippos do, what with all the malaria and dengue fever they spread. I’d also bet that Africans kill more Africans than hippos do, people being people. But like I say, I’m just taking my word for it. I recommend that you do the same.

111708 Never Get Out of the Boat

4:30am came very early, as I suppose it does by definition. M’lady was still alive, but just barely, having spent much of the night in the throes of retching illness. Her insides were scattered about the encampment and her stomach muscles were extremely tender due to her near-continuous expulsion. In the pinnace the crew had moved the hanging out/dining table and laid several mattresses in its place so m’lady could recline in malaise in the belly of the boat. Lying there with her arms crossed over her chest made her look like she was starring in a funeral pyre. Though she claimed to be feeling better than she’d felt during the night it looked like it would be some time before she’d be back to 100%. And so with sleepy cobwebs still clinging to our malrested minds we set off upon the Niger River under the cover of inky night. By the time the sun was ready to rise we had entered Mali’s “Great Lake”, Lac Debo, a body of fresh water so large that you could mistake it for an ocean.

Eager to show off this natural wonder, our captain chugged his pinnace straight to the middle of the fifty-mile-wide lake. Once we’d gotten as far from either shore as we could be the captain cut the engine and spread his arms to the horizon on all sides, urging we tourists to marvel at the sight.

While I’m certain the vast view of open water must be quite thrilling to the desert-dwelling locals, to a guy who has spent most of his life living a relative stone’s throw from the actual Great Lakes it wasn’t all that impressive. To be honest, I found the choppy water that was generously breaching over the gunwales of our small boat to be much more engaging than the view of the horizon. Sure, floating forty kilometres from shore dramatically lessened the danger of a hippo pinnace-flipping but at the same time it seriously upped the risk of large, sea-like waves swamping our tiny vessel.

As we tossed from side to side I cast a glance around m’lady’s unwavering torso resting in the bottom of the boat and tried to assess the lifejacket situation. From what I could see everything seemed to be predictably inadequate and obviously outdated. I tried hard not to look too concerned, with what I suspect was modest success. Regardless, m’lady seemed too ill to notice.

I’m not sure if the captain shared my concern or simply read it on my face, but either way he ordered the crew to light up both engines and get us to the mouth of the river as quickly as possible. This was the only time on the entire trip that he would use both motors simultaneously; normally the long days of virtually non-stop travel were spent alternating between the two. Arriving safely in the calm water close to shore we enjoyed a small breakfast (m’lady abstained), after which I poured a cup of coffee and turned my attention to the riverbank where the colourful and varied wildlife would give an ornithologist a woody.

As we floated idly, the crew busied themselves disengaging one of the engines and lifting it out of the water. They set it down in the galley near the back of the boat and crowded around, all of them poking at it and scratching their heads. Hammerless and forced to be resourceful, the men removed one part of the engine and used the heavy clunk of metal to pound away at another part of the engine. Then they moved in for another round of prodding and head-scratching.

Though m’lady seemed to be improving with every hour, for her sake I hoped our day’s twelve-hour trek wasn’t going to be inadvertently extended by this engine trouble. At the same time I was quietly overjoyed that we weren’t going through this whilst still bobbing away out there in the middle of the turbulent lake. Fortunately the men were able to beat the right engine part into the correct submission and in no time at all the motor was coaxed back to working order. They reassembled it in a jiffy and we were soon back on our continuous way along the magical, mystical Niger River.

And still, every time we approached a village it was like the Rolling Stones had just pulled up in a stretch limo. As we puttered along the entire town would come out to greet us, including no shortage of young, topless women (which, I suppose, also happens to The Stones all the time). On the occasions when we would land everyone would be waiting at the dock to shake our hands. The children loved it when I would pick them up and hoist them into the air. I didn’t even think of pulling out my guitar during our stops in these tiny river villages for fear that they wouldn’t let us leave!

It’s possible that the people dropped what they were doing and rushed to the shoreline hoping us rich white tourists would throw them a small cadeaux, but I’m not convinced that is so. Rather, I suspect it was simple curiosity, and mostly boredom. It seems the main activities ‘round these parts revolve primarily around either mortar and pestling, tossing couscous into the wind, beating dirty clothes against riverside rocks, or goat-herding. And even these activities, difficult as they are, don’t seem to occupy too many people for too long. In the small villages school doesn’t appear to take up anyone’s time nor does any serious sort of commerce, for neither exists in any visible form. Perhaps without too many dollars to spread around in the first place the fight for the mighty buck slips a few notches down the priority list.

But what do I know about it?

And then, finally, our ride up the river was over. Our pinnace pulled ashore in Mopti and we were led to a hotel where showers and restaurant menus and most importantly cold-beers-without-walking-two kilometres-through-the-dark-jungle-to-get-them were the order(s) of the day. After several long, hot days and just as many nights spent sleeping on the hard ground our sparse and somewhat dingy hotel felt remarkably decadent, though I sure did miss the river view.

After nearly forty boat-hours spent floating past basically the same scenery you’d think that I would have started boring of it, but I didn’t. Not for a moment. In fact, I had to force myself to look away long enough to get through the Conrad book, which was a great read and mercifully short, plus it supplied m’lady with the perennial joke “Oh, the snorer…” referring of course to yours truly.

It was the same for the ten-hour bus ride and the day-long 4×4 trip as well. Everywhere I cast my eyes I am fascinated by all that I can see. Something about Mali draws my rapt attention, and I can only conclude that it has to do with the very resonance of this part of the Earth. This is the motherland, and I can sense it. Culturally, one could argue that I have no right to feel at home in Africa but really, I can’t see that race needs to play a part in it. This is where the precursors of humankind first crawled out of the water, and I am human. History pegs West Africa as the grandfather of almost all of the world’s modern music, and I am a musician. Whatever creates the connection, the connection is undeniable. I know that this will not be my last trip to Africa.

As we fell onto our soft bed marvelling in the air-conditioning and making dinner plans we agreed that the best move would be to chill out here in Mopti for an extra day before we embarked on our next adventure. That way we could relax, do some laundry, and maybe even find some local live music. At the same time we knew that were ultimately at the mercy of our man Baba, the fellow we’d met at the airport back in Bamako who had taken a large yet reasonable wad of our money in exchange for arranging all of these excursions, rides, and hotels, and Baba had yet to inform us when we’d be leaving for our tour of the Dogon Valley. Only time would tell so we hedged our bets and sent our clothes out to be washed.

After a long, languid shower and another bout of relaxing we climbed up to the rooftop bar/restaurant and pondered the menu under a star-filled sky. It was with a dream-like fervour that I pointed to the beef skewers with roasted potatoes; m’lady ordered the fish. I quenched my drooling foretaste with several slurps of frosty lager and the two of us sat numb with anticipation, drifting together into a quiet bliss as we waited for our supper.